Women can play significant architectural roles as clients as well as architects – Alice Hampson discusses the influence of the colourful and eccentric Ethne Pfitzenmaier.

Portrait of Ethne Pfitzenmaier.

Alice T. Friedman points out that, between 1919 and 1963, a significant number of the most important houses by prominent architects of the twentieth century “were designed for women clients or for non-traditional, woman headed households”.1 The most famous include Frank Lloyd Wright’s Barnsdale House (1919–23), Gerrit Rietveld’s Schröder House (1924), Le Corbusier’s Villa Stein-de Monzie (1927), Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House (1941–51), Richard Neutra’s Constance Perkins House (1955) and Robert Venturi’s mother’s house (1963). In Australia, the corresponding most celebrated house of that period was by young Austrian émigré architect Harry Seidler for his mother, Rose (1947–1950), at Turramurra in New South Wales.2

Relative affluence and headship of their own households are the circumstances which these women had in common. They turned to architects to design for their needs. The resulting architectural responses were individual houses which, to varying degrees, challenged the established programmatic norm. The architects chosen by these women were seen as avant-garde, and were possibly chosen for their ability to fulfil the clients’ visions for the lives of their unconventional households.

Friedman notes that substantial discussion of the role of women clients is “[n]otably missing from the history of modern architecture” and contends that redressing this omission “results in a narrative strikingly different from the familiar surveys of architecture”.3 Two projects by Eddie Hayes of Hayes & Scott – the emerging young force of Queensland architecture in the early 1950s – are cases in point. Both were for the same client, Ethne Pfitzenmaier: the Pfitzenmaier Herston House and the Pfitzenmaier Beach House. Largely overlooked, they warrant respect and attention, not only for their intrinsic significance as outstanding examples of local domestic modernism, but also as pre-eminent illustrations of Friedman’s thesis.

The client.

Ethne Mary Pfitzenmaier, née Edwards, was born in Sydney on 15 May 1907. She was the eldest of three, with two younger brothers, four and twelve years her junior. Her mother, originally from New Zealand, moved to Sydney and married her father. He deserted his family, leaving Ethne (as the eldest) to go into the workforce to support her mother and young brothers. As the family breadwinner from an early age, Ethne took a dominant role in the household, and had next to no time or interest to devote to the household skills usually expected of a woman in that era – an experience which shaped her whole life. When Ethne’s mother moved with Ethne and the boys to Brisbane to seek out a new life, it was through Ethne’s first Brisbane job as an optometrist’s receptionist that she met Francis John Pfitzenmaier.

Francis, seventeen years Ethne’s senior, was born in Rockhampton on 24 October 1890. The Pfitzenmaier family originated in Stuttgart, Germany, and in the 1860s ran bullock teams from Rockhampton to Normanton. The family later moved into hotels and accumulated considerable wealth. After leaving school at nineteen, Francis set up a successful mercery business in his grandfather’s Rockhampton Hotel, moving to Brisbane in 1927 to manage the family’s hotel interests. He purchased “Berks Corner”, a building on the corner of Albert and Queen Streets, where the tenants included Ethne’s employer, and one of Ethne’s duties was to deliver the optometrist’s rent to Francis.

After Ethne and Francis married in 1928, they resided in hotels where she had no opportunity to acquire or utilise domestic skills. They worked their hotel businesses together – initially the Scarborough Hotel for two years, then the Currumbin Hotel for four or five years. When the Great Depression hit, Ethne and Francis suffered enormous financial setbacks and lost everything. But they rebuilt their hotel businesses, first with the Stock Exchange Hotel in Ipswich, and finally the art-deco-styled Grand Central Hotel in Queen Street, Brisbane.4

By 1939, they had turned the business around and were very wealthy and successful. Although the Grand Central was leased from Queensland Brewery (now Carlton United) they provided £8000 cash to furnish the hotel. Ethne became an extravagant and stylish woman.5 Both she and Francis moved in fashionable Brisbane circles, and were friends of the young architect Eddie Hayes’ parents. But she had worked from a young age, and continued to work until her retirement in 1964 at the age of fifty-seven. She died ten years later.6

Ethne’s ideals of home life were anything but normal. They originated from her days as breadwinner for her mother’s single-parent family. Throughout married life she lived with her husband, and then their two children, in hotel apartments. Francis believed that hotels were not places for children, so they were sent off to boarding school from as early as four-and-a-half years, which also enabled Ethne to run the hotels.

The hotel accommodations consisted of bedrooms with a bathroom and a small living room. There was no kitchen – meals were prepared by the hotel staff and served to the family in the hotel dining room or lounge. This ritual varied only between 1943 and 1945, when the US Navy took over the top floors of the hotel to accommodate officers’ living quarters and offices – the family then relocated to a flat, and meals were sent up by Filipino women working in the hotel kitchens.7 During this period much of the hotel silverware went missing: supposedly, Navy personnel were used to throwing out items from portholes, so they just wrapped up the knives and forks with the rubbish and threw them out. Fortunately, the US Navy had a contract to replace all missing items at the end of their stay, and the Pfitzenmaiers got a full new set of silverware for the hotel.

This lifestyle was not unique – apart from publicans residing in their own licensed premises, it was not uncommon in Brisbane during the first half of the twentieth century for the well-to-do to live in hotel suites. One prominent example was the pre-war Chief Justice of Queensland, Sir James Blair, who with his wife occupied a suite in the National Hotel at the junction of Queen and Adelaide Streets – then a more salubrious establishment than it had become by 1963, when it was at the centre of a Royal Commission into prostitution.8 Although “CBD living” is today promoted by property developers as a new “lifestyle choice”, boarding and guest houses – some more reputable than others – dominated Spring Hill and other inner-city areas until as recently as the 1960s.9

Nonetheless, Ethne Pfitzenmaier’s life experiences gave her a very different outlook from average Brisbane couples of the post-war era, whose aspirations were driven by the “great Australian dream” to own a freestanding home in the suburbs.10 She would have observed first-hand the changes in social customs and mores resulting from Brisbane’s population being almost doubled through the presence of GIs,11 and the racial and national tensions which developed between white and African-American servicemen, and between Australian and US servicemen, which culminated in the infamous “Battle of Brisbane”12 (which was fought out partly in the public bar of the Grand Central).13 At the hotel – where the traditional clientele included Brisbane’s leading social, political, professional and commercial figures – the changes would have been particularly evident, as gentlemen in three-piece suits and felt hats, and ladies in hats and gloves, were ousted by men in military fatigues and their short-term female companions. As even the most affluent citizens of Brisbane dispensed with domestic servants in an era of wartime and post-war austerity and labour shortages, Ethne would have been one of the few wives or mothers never to have had to cook a meal or do the washing for her family.14

In Brisbane during the first half of the twentieth century hotels were one of the few areas of commerce in which businesswomen could command respect and rise to prominence. Ethne did not lead a traditional woman’s life. She supported her mother and younger brothers from the time she left school; she had neither the time nor the need to learn domestic skills; she married a much older man; she lived her married life in hotel premises were she worked with her husband; she depended upon her staff for all regular domestic chores; she sent her children off to boarding school from a young age.

When Ethne Pfitzenmaier came to acquire her first home, the circumstances were again anything but typical. She bought the property in her own name and commissioned it to be redesigned for a convalescing husband, whilst she once again became the family breadwinner. It was therefore inevitable that she brought to the redesign her own ideals of home living. Like other prominent female clients, the outcome was to “blur the boundaries between traditionally defined private space, domestic space, and work space in unconventional ways[;] … [to produce] renegotiated relations, or redefined relations, both among household members and between the household as a unit and the ‘outside world’[;] … [to] reject and offer alternatives to the conventional typology and conventional structuring of the home”.15

Yet Eddie Hayes’ projects for Ethne Pfitzenmaier differed in some significant ways from the examples of prominent female clients studied by Friedman. Ethne readily fits Friedman’s description of “relatively well-to-do”, having a position of “wealth, privilege and social status … that divides these women as a group from the majority of the population”.16 But both projects for Ethne were quite modest renovations. Atypically, the client–architect relationship did not end with a single project. Of Friedman’s case studies, Gerrit Reitveld undertook two projects for Truus Schröder, the first being the redesign and furnishing of a study room for Truus before the death of her husband Frits; in all other instances examined by Friedman, the client–architect relationship produced only one house, and in the case of Edith Farnsworth and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe the project ended in litigation and an unsatisfied client.17

The architect.

The position of Hayes & Scott in developing a local domestic modernism is second to none. The extraordinary architectural partnership between Campbell Scott and Edwin Hayes commenced in 1946.

Although their work was locally the most influential of the period, it received surprisingly little coverage in the serious national press. The pithy publication coming out of the University of Melbourne, Cross-Section,19 hardly rated them a mention, and seldom did their work appear in publications such as Architecture and Arts or Architecture.18 Only non-professional women’s journals gave their work the recognition which it deserved.19

Both were students of Dr Karl Langer, through whom they became aware of the possibilities of working the ground and site into their projects.20 Both had student work illustrated in Langer’s publication “Sub-tropical housing”.21 The text was the first of its kind, with building illustrations animated by human figures and integrating the full site with the house plans – people mowing the lawn and sunbaking, vegetable gardens, outdoor rooms. More than any other architects of the period, Hayes & Scott realised Langer’s inspiration, creating Queensland’s most revolutionary housing of the immediate post-war era.

Hayes & Scott divided the projects in the office very clearly as either a “Hayes project” or a “Scott project”, and the range and types of houses which emerged were bifurcated in characteristics. Hayes was generally seen as the more flamboyant of the two, with fast cars and a wealthy background. His parents owned Greddens, Brisbane’s iconic fashion house of the post-war period – the crème de la crème fashion boutique of the day, which not only designed its own items for wholesale and retail sale, but also stocked garments from other designers in its boutiques throughout Queensland and New South Wales.22 He attended the Julian Ashton Art School in the Queen Victoria Building in Sydney, and was remembered by Ethne Pfitzenmaier’s son as one of the first persons to undergo a psychological test to find out what would best suit him as a career (since he was unsure) – architecture won out over art.23

Ethne Pfitzenmaier was to be Eddie Hayes’ first significant female client, but not his last.24 Through his family connection with Greddens fashion boutique, his own standing as a “young turk” amongst Brisbane’s insular avant garde artistic community of the post-war era, and the support of Mrs Whitfield (editor of the popular women’s magazines Home Beautiful and House and Garden), he was to become the “darling” of an upwardly mobile and socially influential female clientele.

The Pfitzenmaier Herston House.

In 1947 – a year after the inception of the Hayes & Scott practice – the enormous pressure of running the hotel finally had a disastrous effect on Francis Pfitzenmaier’s health and he suffered a stroke. Ethne chose for his convalescence a large single-level stucco brick house at 9 Clyde Road, Herston, with a gabled, tiled roof and porches along the north, south and east. It was situated on large grounds facing Ballymore fields, with a terraced grass tennis court and substantial trees along its western frontage.25 She commissioned Eddie Hayes to renovate it for her husband’s recuperation and rehabilitation, and so that they might both be relieved from the stresses of the hotel. This was to be the first (and last) home that the family would share.

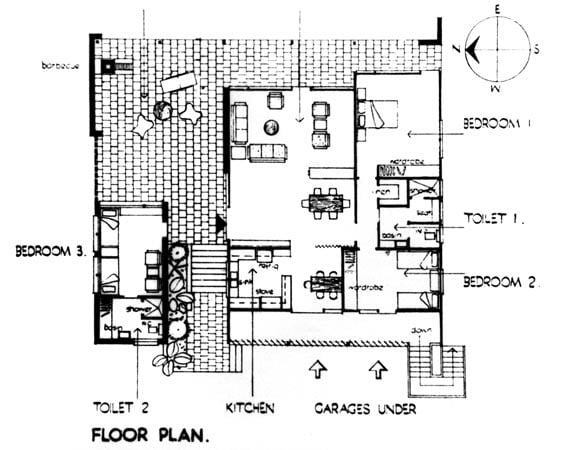

The renovations required a suitable living place for Ethne’s convalescing husband and her two children – Louis, then eighteen, and his fourteen-year-old sister, June. The remodelling was modest but strategic in terms of fashioning a family home to suit Ethne’s aspirations and beliefs in family life. After years of having the family’s domestic needs serviced by the hotel staff, Ethne finally had the chance to realise her own domestic choices. These renovations were significant in two aspects: first by making a household place for Ethne as the central force within the family, and secondly by establishing a level of independence and privacy between family members. The design achieved these objects with both planning and technological innovations.

The arrangement of the children’s rooms fostered independence. Louis had his own suite of rooms, his own bathroom, and a place to park his car outside his room. His sister June’s room, although adjoining her parents’ room, had its own enclosed verandah retreat. There was a family sitting room with rounded windows to the north that overlooked Ballymore grounds. All occupants had their own external spaces, the children had their own entry and the parents had additional separate workspaces and private places, some made by enclosing previously open porches. The hierarchy of public and private spaces was uniquely adapted to a family which had not previously shared a home.

The renovated kitchen was to be Ethne’s first and was the centre of the household. After years of acquaintance with industrial quality technology and having travelled to America where she had seen the latest innovations, Ethne equipped her combined kitchen and laundry with a top of the range oven, a dishwasher and a Bendix front-loading washing machine.26 Cars were housed in a separate structure at the street front, with a separate loggia to the north-west for Louis’ car.

Tragically, the family was to spend only a little under two years in the remodelled home before Francis died in 1949.

The Pfitzenmaier Beach House.

In 1950, the year after Francis Pfitzenmaier’s death, Ethne bought a beach house called Berkeley Square on Garfield Drive at Surfers Paradise. It was an old timber and fibro house set high on a brick base directly facing the ocean. The family spent a number of holidays in the old house before Ethne commissioned Eddie Hayes to renovate the building into a holiday home for herself – by then a professional single woman – and her two children.27

The result was a “breakthrough” building for a new domestic modernism, arguably the best domestic work produced by Hayes & Scott, and certainly (at least in this writer’s opinion) the most significant. It was the firm’s first butterfly roof house and the first of its type in Queensland.28 It won the Queensland Award for Meritorious Architecture in 1953, competing against another of the firm’s beach houses, a house by Prangley and Croft, as well as thirty-one other houses.29 The awards program in Queensland was then at its best.30

At Ethne’s insistence, demolition and rebuilding commenced without proper approval. Later, rather than meeting the building inspectors at her hotel and offering them a bottle of whisky as a truce, she opted to go to court and pay the necessary fine.31 Plainly the project was of particular importance to Hayes, who produced for the client a handsome hand-bound folio of photographs, with a hand-lettered title page which he autographed.32

In an article entitled “Four houses of more-than-usual interest”, Architecture and Arts and the Modern Home of May 1955 offered its readers this description:33

This refreshing butterfly-roofed house on the Surfers’ Paradise seafront … by Brisbane architects, Hayes and Scott, shows the trend developing on Queensland’s South Coast.

The house has white vertical louvres at eye level on the cantilevered balcony, to shade rooms from the north-western sun without restricting the south-west view to the border mountains. A central breeze-way separates a bed-sitting room (with its own bathroom) from the living quarters. Scattered stone and a lone, windswept tree give the lawn a casual look.

Facing the sea, the house takes on a mature look. Under a wide verandah, glass walls open up the living area to the view, and connect the barbecue with the main body of the house.

The beach house design began where the Herston House finished, with a plan that redefined the relationship between parent and (adult) child, and created a domesticity that was both spatial and physical. Within a relatively modest footprint, Hayes created an entirely separate suite of rooms for Louis, linked to the main house by an outdoor room, all united under the butterfly roof.34

The external space between the two sections of the house became the fulcrum of a carefully orchestrated processional route from the street – the visitor approached up a staircase parallel to the main body of the house, climbed to a level somewhat higher than the adjacent sand-dunes, then turned to be confronted with the revelation of seascape framed by the two structures and cradled under the butterfly roof. The essential theatricality of this procession culminated in the outdoor room which, like a stage with a natural backdrop, offered access both right and left to the respective segments of the house.

The same external space also achieved climatic objectives, functioning as a breezeway to ventilate the structures on either side, and affording access to a private barbecue area sheltered by a brick screen wall and a battened continuation of the main roof, but open to the beach. With the external room at the floor level of the adjoining public rooms, it also served as an extension to the limited public space, and provided occupants their route to the sea.35

Viewed from Garfield Drive, the most striking feature of the house was the way that the extension cantilevered over the original structure (which was retained as garages and storage space), clearly identifying the junction between old and new, between utilitarian and intimate spaces. Yet from the beach, only the extension was apparent above the level of the sand-dunes, with a wide covered veranda as a reinterpretation of a traditional Queenslander.

Campbell Scott described his partner’s work as “a whim and fancy, a structural delight”.36. This was reflected in many innovative, and sometimes jocular, features – the doubled columns in the main living space; the internal ceiling which expressed the form of the butterfly roof, and was accentuated by triangular glazing juxtaposed against a horizontal pelmet with concealed lighting; the placement of windows to provide unexpected glimpses of the ocean view; the trademark Hayes & Scott chimney-stack applied to the external barbecue; the retention of a solitary banksia in a landscape recreated with stone and rock;37 the placement of walls and rails to accentuate the view, including low brickwork on the ocean side of the terrace which also served as a seating space; the use of polished hardwood floors throughout the interior, with vinyl tiles only in the kitchen; the striking composition of vertical and longitudinal shades and shadows, of sunhoods and slatted sunshades.

Scott confirms that the design was heavily influenced by Le Corbusier’s Maison de M. Errazuris (1930) in Chile, and recalls Hayes making reference to this work during the design.38 The influence is unmistakeable, if largely superficial. The butterfly-roofed Errazuris House also has significant climb through the building, in the form of a ramp, and manipulation of the Pacific Ocean views. It is divided into two sections, though the division is not complete – in reality it is an L-shaped building with a bridge between the two parts. It is embedded into sloping terrain although the Chilean site is much more dramatic and presents a similar sheer wall edge.

These design features do not, however, detract from the fact that the Pfitzenmaier Beach House was very much the product of the client’s brief. As in the Pfitzenmaier Herston House, the kitchen was of central importance, with a view over the entry route from Garfield Terrace, and again equipped to commercial standards – including the taps and sink, a commercial double oven and upholstered storage spaces. Ethne required separate self-contained quarters for her adult son, though he was (quite literally) accommodated under the same roof. All three members of the household – including her daughter June – had private external areas adjoining their respective bedrooms, and it was intended that they should have separate external access, though a staircase which would have given access to the balcony adjoining June’s room was apparently never completed.39

Sadly, the Pfitzenmaier Beach House – like the Pfitzenmaier Herston House – did not prove to be the enduring family haven that Ethne planned. Louis Pfitzenmaier candidly admits that he never liked it, preferring the modest original house which was largely demolished in the course of Hayes’ “renovation”.40

Financial pressures forced its sale after only three years; it was subsequently demolished to make way for an uninspired multi-storey unit development.41 This might suggest that Ethne’s grand vision of a family holiday home which could be shared on roughly equal terms by a widowed woman and her two adult children was a failure; or it might only suggest that her vision produced the right house for the wrong family. Either way, the failure of Ethne’s vision cannot be blamed on Hayes – his outstanding realisation of that vision demonstrates the validity of Friedman’s observation that “the woman-headed household … is not only a viable social entity but also an architectural entity, worthy of carefully considered design response”.16 Whilst the architectural credit belongs entirely to Edwin Hayes, such an extraordinary and far-sighted design could not have been achieved but for the inspiration of such a colourful and eccentric client as Ethne Pfitzenmaier.

This essay was first published in the book Hayes & Scott: Post-war houses, edited by Andrew Wilson (Brisbane: University of Queensland, 2005). It is reproduced here with permission and thanks to Andrew Wilson.

- Alice T. Friedman, “Not a Muse: The client’s role at the Rietveld Schröder House”, in Diana Agrest, Patricia Conway and Leslie Kanes Weisman (eds), The Sex of Architecture (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996) p. 217. See also Alice T. Friedman, “Shifting the Paradigm: Houses built for women” in Joan Rothschild (ed.), Design and Feminism (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1999), p. 85 and Women and the Making of the Modern House (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998.)[↩]

- Rose Seidler House, in northern Sydney bushland: see D. L. Johnson, Australian Architecture 1901–51: Sources of Modernism (Sydney: Sydney University Press), pp. 180–181; Harry Seidler’s first monograph, Houses, Interiors, Projects, Sydney: Associated General Publications, pp. 2–11.[↩]

- Friedman, 1996, p. 217.[↩]

- J. P. Donogue Architect with C. W. Fulton are said to have built over the site of an existing hotel, now the site of the Hilton Hotel. Liquor licences were and still are extremely limited and utilising a continuing liquor licence with a new structure was the norm for Brisbane hotels.[↩]

- According to Ethne’s son, Louis, she would take thirteen hats to Sydney for a trip lasting twelve days: recorded oral history with Louis Pfitzenmaier, 2 September 2002.[↩]

- Ethne Pfitzenmaier lived out her retirement in Camden, a ten-storey forty-unit block of flats at Hamilton by Bligh Jessup Bretnall & Partners; see Cross-Section, no. 77, March 1959.[↩]

- Oral history with Louis Pfitzenmaier, 18 March 2004.[↩]

- Queensland Law Reports (Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for the State of Queensland), Queensland Weekly Notes – Notes no 28 and 29 for 1964.[↩]

- Alice Hampson, The Fifties in Queensland: Why Not! Why? Bachelor of Architecture thesis, University of Queensland, 1987, p. 116. By 1957 the Building Ordinances, Chapter 18, still had no provision for home units.[↩]

- Robin Boyd wrote in his original edition preface of Australia’s Home: Why Australians Built the Way They Did (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1951): “Australia is the small house. Ownership of one in a fenced allotment is as inevitable and unquestionable a goal of the average Australian as marriage.”[↩]

- Radical Brisbane: An Unruly History, (Victoria, The Vulgar Press, 2004) p. 206.[↩]

- See Peter A. Thompson and Robert Mackie, The Battle of Brisbane: Australians and the Yanks at War (Sydney: ABC Books for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2000).[↩]

- Recorded oral history with Louis Pfitzenmaier, 2 September 2002. Louis recalls that the rioting servicemen arrived at the Grand Central to demand a keg of beer, and his father obliged them. They returned later to demand a spear and other implements to tap the keg, and again Francis acceded. Only when they returned for a third time, demanding glasses, were they refused – so they moved on to another hotel, which they proceeded to trash.[↩]

- J. M. Freeland, A History: Architecture in Australia (Ringwood: Penquin Books Australia, 1972) p. 265.[↩]

- Friedman, 1999, p. 85.[↩]

- Friedman, 1996, p. 218.[↩][↩]

- Friedman, 1996, p. 224.[↩]

- Cross-Section started in November 1952, and was originally entitled Cross -Section: A Private Communication to Architects and Master Builders. The journal was published by the Department of Architecture at University of Melbourne and it ran for just under twenty years. Architecture and Arts also started in July 1952, and was a name reversal of the Californian publication Arts and Architecture. Arts and Architecture was edited by John Entenza between 1943 and 1959 and led to the Case Study House Program. Architecture and Arts during the 1950s had the added title of and the Modern House. On 18 August 1930 a national federation of architects, the Royal Australian Institute of Architects, was formed. A draft document, “The Agreement of 1930”, was drawn up and published in the federation’s journal, Architecture, vol. 22, no. 1, in 1933. By the mid-1950s the journal was called Architecture in Australia.[↩]

- Especially Home Beautiful and House and Garden, locally edited by Mrs Cynthia Whitfield. Hayes & Scott also designed a house for Mrs Palfreyman who was editor of the Queensland magazine Country Life. Scott recalls designing a house specially for publication in Country Life for Mrs Palfreyman. Scott and Hayes often stated that local architects were so interested in publications for ideas that “Brisbane was only as good as the last magazine”: Brisbane driving tour and interview with Campbell Scott, Don Watson and Fiona Gardiner, 16 January 2001.[↩]

- Karl Langer biography in Hampson, 1987, Appendix A, p. 201.[↩]

- Karl Langer, “Sub-tropical housing”, University of Queensland: Faculty of Engineering Papers, vol. 1, no. 7, May 1944. Campbell Scott designed Plan No 8 on Plate 6 of Langer’s publication. Hampson, 1987, p. 110.[↩]

- Eddie Hayes’ mother, Kathleen May, at seventeen years lied to a bank manager about her age to secure a loan to set up a fashion business in Brisbane after achieving some success in designing women’s clothing while living in Roma. She had enormous flair and talent as a designer and, with her two elder sisters, started a fashion dynasty that led to her designs being retailed through eighty boutiques throughout New South Wales and Queensland by the late 1960s. The business Greddens was headquartered for many years in what is now the Sportsgirl Building in Queen Street, Brisbane. Interview with Campbell Scott, 21 June 2004. The main Greddens stores in Queen Street, Brisbane, and King Street, Sydney, were designed by Eddie Hayes. The designs were published in the RAIA publications Buildings of Queensland and Architecture. Hampson, 1987, p. 124, catalogue nos 03/1951/14, 03/1952/15.[↩]

- Eddie Hayes recalls William Dobell who was painting his Archibald-winning portrait of Joshua Smith being a regular at the studio where Hayes was being taught by Ashton. Recorded oral history with Eddie Hayes, Don Watson and Alice Hampson, 13 April 1989, held at Fryer Library, University of Queensland, hereafter citied as “Hayes, 1989”. Recorded oral history with Louis Pfitzenmaier, 2 September 2002.[↩]

- Interview with Louis Pfitzenmaier, 18 March 2004.[↩]

- Louis Pfitzenmaier recalls immediately planting the trees along Clyde Street: interview, 18 March 2004.[↩]

- In 1938 Ethne went on a trip to America with friends: recorded oral history with Louis Pfitzenmaier, 2 September 2002. From the late 1930s right through the 1950s Australia was heavily influenced by America, with newspapers covering all manner of things American, like “So this is America”, an article in The Courier-Mail (14 July 1945) that covered the results of America’s nation-wide architectural competition for the ideal family home. The leading department store McWhirters regularly advertised “American” clothing and items “made on American lines”: The Courier-Mail, 14 November 1945. There is disagreement as to Ethne’s proficiency as a cook: her son Louis remembers his mother as a culinary wizard (interview with Louis Pfitzenmaier, 5 February 2003), but Campbell Scott recalls an occasion when he and Eddie Hayes were invited to dine with the Pfitzenmaiers, and Ethne managed to explode the pressure cooker (interview with Campbell Scott, 21 January 2003). A similar dichotomy of recollection relates to Ethne’s skill as a motorist – Louis recalls her as an exceptional driver, Campbell remembers her as an exceptionally bad driver. In either view, Ethne was definitely a woman of character.[↩]

- Eddie Hayes stated the house was not an extension. Hayes called the house and landscape “the most ambitious one”, and found it “a horror to design a house the form of which was dictated by the old shack on top. The foundations became the garage”. Hayes, 1989.[↩]

- Later in 1957, the Graham House, Harts Road, Indooroopilly, had a butterfly roof, although in this case the roof unified the sleeping and living areas (rather than separating them under the butterfly roof’s open spine); it also provided a covered outdoor extension to the living space. Robert Riddel, “Design”, in Rod Fisher and Brian Crozier (eds), The Queensland House: A Roof over Our Heads (Queensland Museum, 1994), p. 61.[↩]

- Architecture and Arts and the Modern Home, April 1955, p. 16.[↩]

- In 1939, the Queensland Chapter of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects held its first architecture awards in Brisbane. Enthusiasm for the inaugural awards saw the event repeated in 1940, but the program was suspended during the Second World War and it did not resume until 1948. During the 1950s, awards were not held between 1954 and 1957, and the event was again missed in 1959. Thus, in the two decades from 1939 to 1959, what had been conceived as an annual event occurred on only nine occasions. In years when there were no awards, it was either because the number of entries, or their quality, was deemed insufficient, or simply because no nominations were called. From unfinished manuscript, Alice Hampson Masters thesis.[↩]

- Interview with Louis Pfitzenmaier, 21 January 2003.[↩]

- The existence of this extraordinary artefact was unknown to his partner, Campbell Scott, until it was discovered to be in the hands of Louis Pfitzenmaier, in the course of research for this article; nor was he aware of any other project for which a similar folio was made: interview with Campbell Scott, 13 March 2003.[↩]

- The Pfitzenmaier Beach House was, in fact, the only one of the “Four houses of more-than-usual interest” that was constructed. The house at Beaumaris by Douglas D. Alexandra, illustrated as a drawing in the same article, has similarities (square plan, form and pyramidal roof) to Hayes & Scott’s 1957 Jacobi House designed by Campbell Scott. A preview of the house also appeared in the same journal’s issue of April 1955.[↩]

- Whilst current building regulations restricted the size of new domestic constructions, there was no such control in relation to renovations of existing houses: see National Security (Supplementary) Regulations, Regulation 31A, which placed a complete ban on the erection of new dwellings unless a permit was granted. Annual Report of the State Advances Corporation, in Queensland Parliamentary Papers, 1944/5; Hampson, 1987, p. 59.[↩]

- Influenced by the teachings of Dr Karl Langer, particularly the integration of inside and outside to produce greater floor plans, as illustrated in Langer, 1944.[↩]

- Interview with Campbell Scott, 5 February 2003[↩]

- Louis Pfitzenmaier recalls that, when the rocks were delivered on site from the riverbed at Currumbin, his mother was disappointed that they were too small: recorded oral history with Louis Pfitzenmaier, 2 September 2002. Eddie Hayes said, “Landscaping was a South American precedent from Roberto Burle Marx.” Hayes, 1989.[↩]

- Interview with Campbell Scott, 4 October 2003. Maison de M. Errazuris was designed by Le Corbusier, but executed without his knowledge, on a site overlooking the Pacific Ocean: Willy Boesiger, Le Corbusier, (Barcelona: Editorial Gustavo Gill SA, 1972), p. 70; see also Dr H. Girsberger, Le Corbusier und Pierre Jeanneret Ihr Gesamtes Werk von 1929–1934 (Zurich: Imprime par les Arts Graphiques Schüler, 1935), pp. 48–52. In the recorded oral history with Eddie Hayes, he recalls the influence of Oscar Neimeyer in Brazil: Hayes, 1989.[↩]

- The staircase is shown in every published plan of the Beach House. During the holidays Louis remembers his friends frequently counting more than thirty-two people visiting the house in a single day. Possibly so public was the house that the nerve behind the design of another access point for the house was scrapped for security reasons. Interview with Louis Pfitzenmaier, 21 January 2003.[↩]

- Interview with Louis Pfitzenmaier, 5 February 2003. It seems that Louis’ dislike of the Garfield Terrace house is attributable, at least in part, to the fact that his mother expected him to drive to the Gold Coast and check on the condition of the house after every storm.[↩]

- ibid.[↩]